We Are Looking For Products You Search

When well cared for, hydraulic cylinders should last decades. So long as they were designed for their application — meaning they perform within the bounds of their environment — there should be no reason for damage or wear outside of regular use. The mount, rod and raw material should have been selected to best suit the cylinder’s purpose. If your machine was not so lucky to have been designed by a thoughtful engineer, ask yourself if constant failures are the result.

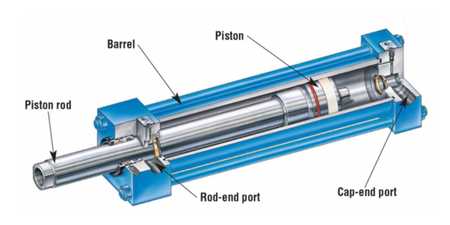

The steel and synthetic rubber construction of hydraulic cylinders make them highly durable. The head, cap, flanges and mounting fixtures are all made from steel. The piston rods use high tensile chromed steel, while the tie-rods use elastic steel trademarked as Stressproof that is both strong and elastic. Finally, the “wear” components must be alternate metals to prevent galling, so bronze and cast iron make the top choices for bearings and pistons, respectively.

Some exceptions to infinite repairability do exist, however. Just like your vehicle, sometimes the cost of repair warrants an entirely new cylinder. Your off-the-shelf “farm” duty cylinders may cost more for a technician to inspect, let alone replace. Also, some larger implement cylinders with welded bodies may only make sense to repair the gland, rod and piston assemblies. Should the barrel with its welded mount fail catastrophically, it’s best to replace the entire cylinder.

A high-quality NFPA, mill-type or high-quality custom cylinder almost always warrants a repair. The comparison to a new car is valid since I often find myself looking at a cylinder imagining the car I could purchase with the same dollar value. With the car comparison in mind, it almost always makes sense to repair rather than replace So many local hydraulic shops make their ends meet from repairing cylinders, so you get the idea just how repairable they are. NFPA and mill-type especially were designed with repair in mind. NFPA cylinders employ square caps spanned and fixed to a barrel using tie rods. These tie-rods are threaded into the cap or head, typically on one side only, while the opposing side gets torqued down with a high-strength nut. Removing the nuts and tie rods makes quick work of cylinder repair because the entire assembly easily (usually) comes apart. Mill-type cylinders enjoy the same level of repairability, except for different reasons. Rather than tie-rods compressing the cylinder assembly, a mill-type cylinder uses flanges welded to either end of a heavy-duty barrel and the head and cap bolt to the flanges. Mill cylinders may be more complicated than my simple explanation, but the takeaway is their repairability equals NFPA cylinders. In fact, mill-type cylinders may be repaired will still fully or partially installed in the machine.

Regardless of the type of cylinder in for repair, hydraulic shops operate using similar procedures to diagnose, quote, and then repair your cylinder. Upon arrival at the repair facility, the first step is to log the cylinder into the shop’s ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) software and then provide a visual method of identifying the cylinder as it moves through the repair process. It helps when you provide as much information to the shop as possible, including the machine number, the cylinder function, and perhaps references to previous repairs.

Using the relevant cause of failure information written on the work order, if it exists, the technician working on the repair starts with a visual inspection of the cylinder. They’re looking for apparent physical damage, such as a bent rod, broken threads, damaged tie-rods or anything other obvious sign to start their diagnosis. A bent rod, for example, requires a unique approach to repair. A bent rod prevents removing the gland or bearing assembly, so the head must be disconnected from the barrel assembly allowing the technician to pull the entire piston-rod assembly out. The piston must be removed to allow the bearing-containing head to slide back off the rod.

If no such apparent damage exists, the technician rightfully assumes the problem stems internally. Most cases of cylinder repair require just the replacement of seals if you’re lucky. The next step is disassembly, where the technician removes and inspects each component of the cylinder. What the technician sees from the disassembly process often helps with the diagnoses of machine problems well.